You hardly can miss Arrow on your path of learning Haskell. Just after struggling with Functor, Applicative and Monad, you convince yourself that you can finally take a look at those standard libraries requiring you the knowledge of Monad. A few Arrow interface libraries such as Hakyll, HXT, reactive-banana just punch you in the face. You just don’t understand what that is. Finishing tutorials on wikibook (link1, link2) do help, but you still can’t get the whole picture. What’s the relationship between Arrow and Monad? Is there non-trivial concrete example that can persuade me it is useful? Here I try to provide my answers.

Why Monad is not Enough

Arrow is proposed by John Hughes in 1998. As described in his paper Generalising Monads to Arrows, the purpose of Arrows is to resolve the issue of memory consumption in using moandic parser. An example from the paper is:

instance MonadPlus Parser where

P a + P b = P (\s -> case a s of

Just (x, s') -> Just (x, s')

Nothing -> b s)The property of Plus corresponds to backtracking parsers. The input s is retained in the memory and not garbage collected as long as the parser a succeeding in parsing. If a succeeds a large part of the input s before it eventually fails, then a great deal of space would be used to hold these already-parsed tokens. To resolve this kind of problems, the Arrows was proposed.

Besides the issue mentioned above, We know that Monads essentially provide a sequential interface to computation. One can build a computation out of a value, or sequence two computations. The structure of Monads empowers us convenience and at the same time limits its usage. Some problem domains can not be modeled with Monads, jaspervdj proposes that a building system like Hakyll is one of them.

In general, the structure that is not sequental, but is much like electronic circuits can be modeled by Arrows. Monads fails to model these structures. Its composability is not as flexible as Arrows.

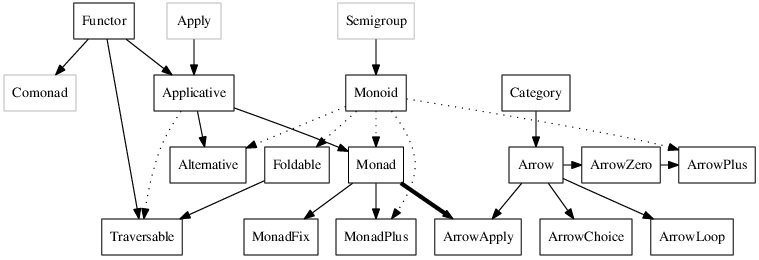

Typeclassopedia

Let’s see a diagram from Typeclassopedia by Brent Yorgey.

This diagram tells us the relationship between Monads and Arrows. Unlike Functor and Applicative, they are basically different things and from different lineage.

First of all, an Arrow has to be an Category. Category generalizes the notion of function composition to the morphisms in Category Theory. Its definition in base package is as follows:

class Category cat where

id :: cat a a

(.) :: cat b c -> cat a b -> cat a cWe can see that it requires an identity morphism id, and the composition operator (.) for morphisms. Also note that Category is unequivalent to arbitrary categories in Category Theory. It only corresponds to those categories whose objects are objects of Hask.

Laying on the foundation of Category, Arrow’s definition is as follows:

class Category a => Arrow a where

arr :: (b -> c) -> a b c

first :: a b c -> a (b, d) (c, d)

second :: a b c -> a (d, b) (d, c)

(***) :: a b c -> a b' c' -> a (b, b') (c, c')

(&&&) :: a b c -> a b c' -> a b (c, c')There are five methods here, but actually you only have to define arr and first. Rest of them can be automatically derived.

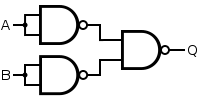

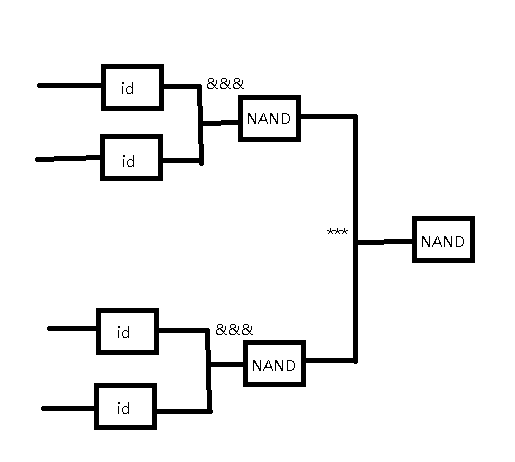

To see how these five composing methods work, let’s try out an easy example. That is to model an OR gate with NAND gates.

We can duplicate the input to the first level NAND gates with id and &&&, and to combine the results of first level NAND gates, we can use *** operator. In chart it looks like this.

To implements it in haskell we also need to define the circuit element as instances of Category and Arrow, we call it Auto.

{-# LANGUAGE Arrows #-}

import Prelude hiding (id, (.))

import Control.Arrow

import Control.Category

data Auto b c = Auto (b -> c)

instance Category Auto where

id = Auto id

Auto f . Auto g = Auto (f . g)

instance Arrow Auto where

arr f = Auto f

first (Auto f) = Auto $ \(x, y) -> (f x, y)

nand2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

nand2 = arr (not . uncurry (&&))

or2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

or2 = ((arr (id) &&& arr (id)) >>> nand2) *** ((arr (id) &&& arr (id)) >>> nand2) >>> nand2

runAutoA :: (Bool, Bool) -> Auto (Bool, Bool) a -> IO a

runAutoA x (Auto f) = return (f x)

main = do

let comb = [(False, False), (False, True), (True, False), (True, True)]

result <- sequence $ flip runAutoA or2 `map` comb

putStrLn $ show resultArrow Notation

When we are tackling larger problems, the notation soon gets complicated to handle. That’s why we want to have do block syntax sugar to make it look nicer, as we do for Monad. GHC provides Arrow Notation, but it’s currently not part of Haskell 98, you must enable the corresponding extension: with -XArrow or prepend a header line to the files {-# LANGUAGE Arrows #-}. After that, we can rewrite our OR gate example above with Arrow notation.

{-# LANGUAGE Arrows #-}

import Prelude hiding (id, (.))

import Control.Arrow

import Control.Category

data Auto b c = Auto (b -> c)

instance Category Auto where

id = Auto id

Auto f . Auto g = Auto (f . g)

instance Arrow Auto where

arr f = Auto f

first (Auto f) = Auto $ \(x, y) -> (f x, y)

nand2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

nand2 = arr (not . uncurry (&&))

or2' :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

or2' = proc (i0, i1) -> do

m1 <- nand2 -< (i0,i0)

m2 <- nand2 -< (i1,i1)

nand2 -< (m1,m2)

runAutoA :: (Bool, Bool) -> Auto (Bool, Bool) a -> IO a

runAutoA x (Auto f) = return (f x)

main = do

let comb = [(False, False), (False, True), (True, False), (True, True)]

result' <- sequence $ flip runAutoA or2' `map` comb

putStrLn $ show result'The pattern is keyword proc followed with the input symbols, then -> do. We describe each elemment in each line. m1 <- nand2 -< (i0,i0) means nand2 accept a tuple (i0, i0) and the its output is bound to the name m1. The last line must be an expression, just like Monad, its value denotes the value of the whole do block. In this case, its the output of nand2 -< (m1,m2)

A More Complicated Example

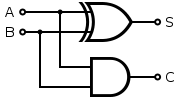

Already know how to simulate OR with NAND, let’s implement a hald-adder.

With the help of Arrow Notation, all we need to do is to define the instances, and drawing circuits with <- and -< symbols in the program.

{-# LANGUAGE Arrows #-}

import Prelude hiding (id, (.))

import Control.Arrow

import Control.Category

data Auto b c = Auto (b -> c)

instance Category Auto where

id = Auto id

Auto f . Auto g = Auto (f . g)

instance Arrow Auto where

arr f = Auto f

first (Auto f) = Auto $ \(x, y) -> (f x, y)

and2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

and2 = arr (uncurry (&&))

or2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

or2 = arr (uncurry (||))

nand2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

nand2 = arr (not . uncurry (&&))

xor2 :: Auto (Bool, Bool) Bool

xor2 = proc i -> do

m0 <- nand2 -< i

m1 <- or2 -< i

and2 -< (m0, m1)

hAdder :: Auto (Bool, Bool) (Bool, Bool)

hAdder = proc i -> do

o0 <- xor2 -< i

o1 <- and2 -< i

id -< (o1, o0)

runAutoA :: (Bool, Bool) -> Auto (Bool, Bool) a -> IO a

runAutoA x (Auto f) = return (f x)

main = do

putStr "Hello "

pairs <- runAutoA (True, True) hAdder

putStrLn $ show pairsPostscript

As you can see from typeclassopedia diagram, there are variants of Arrow. They are ArrowZero, ArrowPlus, ArrowLoop, ArrowChoice and ArrowApply, where ArrowApply is equivalent to Monad. I’ll write another post to introduce them another days.